The Northernmost Land Action of the Civil War

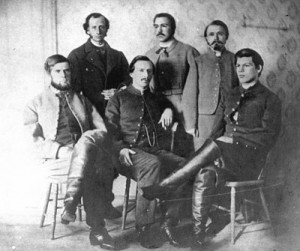

A Feb. 15, 1864 photo showing five of the at least 18 St. Albans Raiders following their escape to Canada and while they were held for trial in Montreal.

The story of the St. Albans Raid of Oct. 19, 1864, has all the makings of a silver-screen drama. In fact, a 1954 movie, “The Raid,” did just that, although it played fast and loose with the facts.

The youthful, dashing and real-life lead character, Confederate Lt. Bennett Young, was the small band’s leader. Young took charge of the mission almost right from the start, recruiting other Confederates who, like himself, had escaped from Union prisons and found their way into Canada.

Once in St. Albans, Young found time to provide company to a young St. Albans woman, and was given a tour of the governor’s mansion by the state’s unsuspecting first lady.

The plan was hatched north of the border, where the Confederacy had bases of operations and sympathizers.

History has alternately recorded the mission’s purpose as: revenge on the North for the Union Army’s ill treatment of Southerners; an effort to supply the Confederacy with much needed cash (more than $200,000 – a monumental sum in those days were taken), and/or to force the North to pull badly needed troops from the front lines.

The rebels, 22, is a commonly given number but only 18 names have been confirmed, arrived in St. Albans in twos and threes over a 10-day period, most by train from Canada.

They blended into the local scene giving various business or travel reasons for their visits.

Accounts of the raid have come from research conducted by St. Albans historians (Carl E. Johnson, Donald Miner, the late Edmund Steele and John Branch, Sr., who as a boy witnessed the raid). The St. Albans Messenger newspaper’s archive holds a day-by-day account of the raid and its aftermath. A number of new books and publications have continued to add insights.

Originally planned for Oct. 18, 1864, the raid was put off for a day as some of the Confederates had just arrived and it was found that activities on that Tuesday – known as market or “butter day” in the village – would complicate the mission.

The next day, by coincidence, some 40 of the villages leading men (and by reputable accounts the county sheriff as well) were to be in Burlington for a Supreme Court hearing, or in Montpelier at the Legislature. So Wednesday it was to be.

Ready For Action

The mood inside Bennett Young’s Tremont House room that afternoon of Wednesday, Oct. 19, 1864 had to have been tense. The five-story Tremont was located on North Main Street where St. Albans City Hall stands today and it was there that the band of Confederates gathered just before their surprise action.

Nine days earlier, Young had come to St. Albans from St. Johns, Quebec with two other Confederates who also took rooms at the Tremont. Much of the planning for their operation had taken place in St. Johns and Montreal.

Others of the party, in order to disguise their objectives, first traveled to Burlington and Essex Junction and then doubled back North, either by train or carriage, to St. Albans. They stayed at the American Hotel at the corner of North Main and Lake streets, and at the St. Albans House at the corner of Lake and Catherine streets, both of which still stand today. Others roomed at The Willard, a boarding house on Lake Street where the Vermont District Courthouse now stands.

Why pick St. Albans? Among other things, even though the state’s governor had sought greater army protection, there were no military units in the area. Also, there were four substantial banks and the prospect of a raid on nearby Swanton as well.

The men had made themselves familiar with their targets: the First National Bank on the south side of Fairfield Street (just one building up from Main Street); the Franklin County Bank, just north of the American House; and the St. Albans Bank, at the southwest corner of Main and Kingman streets.

They had scouted out the full layout of the town that occupied an area a half-mile mile east to west and 2 miles from north to south. Among the 4,000 people living here, they duly noted, were some 600 to 700 employed at the Central Vermont Railway Shops on Lake Street and up to 50 at the adjacent St. Albans Foundry, located on Foundry Street, now known as Federal Street.

The raiders knew that those men, if they were alerted to the assault on downtown, could easily pose a disastrous end to their mission. It was why they would corral people in the main village green and do whatever it took to block anyone from sounding a wider alarm.

The intent had been to rob the banks and ride swiftly to Swanton to do the same there. The pursuit given them by a local group of armed men apparently spared Swanton.

The raiders, all of whom had fought for the South, wore civilian clothing. Each carried a pair of Navy .36 caliber pistols and had a leather kit bag, known as a Morocco satchel, slung over his shoulder. The raiders were mostly young. One was 38, but all the others were between 20 and 26.

The group found its 21-year-old leader praying at his bedside when it entered his room for the 2:30 p.m. meeting. During the last minute planning, Young placed particular importance on those assigned to steal horses, saying they had to be ready with them as soon as the banks had been robbed. Saddles, stirrups, and reins also had to be procured.

The flammable liquid “Greek Fire,” a chemical concoction of clear liquid bottled in four-ounce glass containers, was handed out, one of which was tossed into the washroom as the men left the Tremont. As with virtually all of the combustible liquid (which smelled of rotten eggs) that bottle failed to ignite. The liquid, despite repeated dousing with water, would smolder for the next two or three days.

The Raid Begins

It was cloudy and threatening rain when Young arrived out front of the American House hotel. He stopped and told the several men present there that as “an officer of the Confederate Service,” he was “going to take the town … and shoot the first person that resisted.”Bystanders thought he was joking, but knew better when gunfire and rebel yells filled the air. A church clock’s chime at 3 o’clock was the signal for the robbers to enter the banks.

All hell broke loose after that.

It has been substantiated that the raiders included: Bennett Henderson Young, Squire Turner Tevis, Alamanda Pope Bruce, Samuel Eugene Lackey, Marcus Antonius Spurr, Charles Moore Swagar, George Chrisman Scott, Caleb McDowell Wallace, James Alexander Doty, Joseph Parkhill McGrorty, Samuel Simpson Gregg, William Dudley Moore, Thomas Brontson Collins, William Hutchinson Huntley (referred to as William Hutchinson in local histories and newspaper accounts), William T. Tevis, Louis Singleton Price, John D. McInnis, and Charles Hunt Higbee.

To this list one might add (although evidence of their involvement is circumstantial): John L. Moss, Daniel Mock Butterworth, Charles Travis Daniel, John Louis Mock, and Joseph Fielding Bettersworth.

There also might have been a half-dozen or more co-conspirators who remained in Canada. Young would say in 1911 that much of the planning was done in Sainte-Catherine, an off-island suburb of Montreal.

“I take possession of this town in the name of the Confederate States of America,” Young proclaimed outside the American House. He repeated the declaration and then he and others, armed with pistols, began to herd people across Main Street and onto the village green (today’s Taylor Park).

Some of the witnesses that day said that Young discarded a written text of his just-given speech on sidewalk. If he did, it was never found.

Specific raid day actions were attributed to individual persons. Some St. Albans residents attended court hearings held later in Canada and a small number of raiders’ photographs became available locally. While witnesses put names to faces and newspaper and historical accounts adopted them as fact, it would appear there was ample room for misidentification.

The St. Albans Bank

Cyrus Newton Bishop saw armed men entering the St. Albans Bank and ran to a back office where Martin A. Seymour was working. The men were no match for raiders Collins, Spurr, Price and Squire Tevis.

The raiders quickly pushed through an inner door, which struck Bishop soundly on the head, causing a bruise that lasted for days.

The newly taken hostages were ordered to keep silent, and told their four assailants were Confederate soldiers who had come to take the town and exact vengeance for the plunder Union soldiers had “been doing in the Shenandoah Valley.”

On this same day in Cedar Creek, Va., Gen. Phillip Sheridan and his army, in a counterattack against the South’s Gen. Jubal Early, drove the Confederates from the field and won the battle that later assured the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln. The soldiers of the Vermont 8th Regiment distinguished themselves as heroes in that action.

But in St. Albans, at this moment, the war had come home to roost and Bishop and Seymour were to be in its pistol sights for the next 12 minutes or so.

The robbers, having locked the bank door, filled kit bags and pockets with bank notes found on Bishop’s table and in the safe. However, during these urgent moments, the bandits failed to discover $9,000 in a drawer under the bank counter.

They found $1,500 in bagged silver that was too heavy to carry. They took just $400 of it.

Bank customer Samuel Breck was the first to knock at the locked door. He had come from his and Jonathon Weatherbee’s gentleman’s furnishing store located next door. A raider opened the door, thrust a gun in Breck’s face, pulled him inside, and snarled either, “I take deposits,” or “I’ll take that.”

Breck gave up $393.

Morris Roach, just 17, suffered a similar fate and lost $210 belonging to his employer, Joseph Weeks.

Breck and Roach were forced into the back director’s room where Collins lectured the hostages about Gen. Sheridan and how this day was one of retaliation.

Seymour was cantankerous. He refused to say if there was gold on the premises and demanded time to take an inventory, saying that if this were truly an act of war, the bank would post a government claim to cover its losses.

“Damn your government, hold up your hands,” Collins said. He then forced the Vermonters at gunpoint to “solemnly swear to obey and respect the Constitution of the Confederate States of America” and that they would “not fire on the men of that government then in this town” and further that they would not report the robbery until two hours later.

This humiliating episode apparently became a bit of amusement for fellow raiders. Young, in a letter sent later to the Tremont House (including full payment for his hotel room), said the men could now lower their hands.

Seymour is credited with preventing a much larger theft than the about $80,000 taken from the St. Albans Bank. He diverted the robbers’ attention from an additional $50,000 in cash and an equal amount in new, still-uncut St. Albans Bank notes.

The robbers left more money in the bank than they took, which led some to suspect drunkenness. There were witnesses who reported a “rank atmosphere of alcoholic fumes about the robbers.” However, there was no clear indication that alcohol played a major role in bolstering the raiders’ courage. The effectiveness of their actions would seem to argue the opposite. Perhaps they just smelled of Greek Fire.

The St. Albans Bank heist ended about as suddenly as it had began. The raiders, hearing a report of firearms in the street, began to exit. Two remained moments longer than the others – pointing their pistols at the employees as they backed out the door.

Huntley then moved on to join others at the next bank.

Franklin County Bank

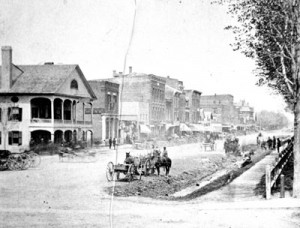

The Franklin County Bank is seen in this photo looking north up Main Street from Fairfield Street. The bank is the building with the rectangular sign on its side. The building to its left, with the elaborate porches, is the American House. It was on the sidewalk in front of it that Bennett Young signaled the start of the raid. At right is the park where residents were held hostage

What happened at the end of the Franklin County Bank robbery is not for the claustrophobic.

Jackson Clark, a local wood sawyer, was in the bank before four raiders, pretended to be customers, entered. Huntley, fresh from the first robbery, arrived and asked cashier Marcus W. Beardsley about the price of gold.

Beardsley said none was sold there and referred Huntley to James Russell Armington who had come in to do some banking. Armington sold two gold pieces to Huntley and left with James Saxe with whom Clark had been talking when the raiders entered.

This left Beardsley and Jackson alone in the bank with the raiders, who then drew their weapons. One of them announced that they were just four of hundreds of Confederate soldiers that were now occupying St. Albans, which they intended to burn.

Clark made a dash for the door, but was ordered back and threatened with death if he were to move again.

Huntley then ordered up “all your greenbacks, bills and property of every description.”

As the loot was being gathered, Clark again made an escape bid and this time was ordered into the bank vault. Huntley then forced Beardsley to join Clark.

The bank cashier argued that the vault was airtight and that to seal them in it was inhumane. Huntley would have none of it, saying, “You are treating people in the South in the same manner.”

The vault door was closed with Beardsley and Clark left to wonder whether they’d be burned alive in the promised torching of the town or simply die gasping for air.

Luckily, soon after the robbery, Armington and Dana R. Bailey entered the bank, heard the captives’ cries and were able to free them. Accounts differ, but either Beardsley instructed the men on how to open the vault, or the rescuers found the key still in the door.

The men had been confined for about 20 minutes and upon leaving the vault saw the raiders as they fled north.

It would later be agreed (there were numerous questions about the banks’ losses in general) that $70,000 had been taken from the Franklin County Bank.

First National Bank of St. Albans

The First National Bank is visible in the distance on Fairfield Street. It is just behind where the men are seated on the bench in the park.

The First National Bank of St. Albans was robbed about simultaneously with the Franklin County Bank. Raiders Bruce, Doty, McGrorty and Wallace were assigned to it.

As the raiders entered, bank clerk Albert Sowles was in the office with a distinguished military man, then nearly 90-year-old Gen. John Nason. Nason had been the head of the Franklin County Militia during the Canadian rebellion of 1837-39. Prior to that he had served as a soldier in the War of 1812.

Wallace and a fellow robber leveled their revolvers on their targets. Sowles made note that Wallace’s hand shook as he shouted, “If you offer any resistance I will shoot you dead.”

McGrorty began filling his pockets with bank bills, treasury notes and U.S. bonds from the safe, tossing some of the latter across the counter to the others. Bruce kept guard at the door.

The nearly deaf old soldier, all sources agree, spent the duration of the robbery reading a newspaper, even though at one point an unnamed raider is reported to have said, “Shoot the old cuss,” to which another responded, “No, he is an old man.”

The raiders were filing out of the bank, loot in their pockets and leather satchels, when St. Albans resident William N. Blaidsdell entered and asked what they were doing.

When told the bank had been robbed, the burly Blaidsdell turned, met an armed raider coming toward him up the steps, seized the Confederate and fell down on him.

Wallace and another raider shouted: “Shoot him! Shoot him!”

Instead, pistols were held to Blaidsdell’s head and he was ordered to give up or have his brains blown out.

It was at this point that old General Nason became fully aware of the ruckus. Standing on the bank steps he mildly suggested that “two upon one” was not “fair play.”

As the robbers forced Blaidsdell into the village common and lugged some $55,000 away with them, Gen. Nason added, “What gentlemen were those? It seems to me they were rather rude in their behavior.”

Questions have been raised over the full amount of the raiders’ take at the First National. Some estimates were as high as $98,000, but the bank eventually settled on a claim of $58,000 in losses. It could have been higher still.

McGrorty, as he pilfered the safe, is said to have asked Sowles about the contents of a number of the bags. He was told they contained pennies. To be certain the raider emptied one of five bags on the floor and only cent pieces rolled about.

He didn’t realize that another of the bags was filled with gold.

In all the losses at the three banks would finally be placed at $208,000. Thirteen raiders would later have $86,000 confiscated from them in total, meaning $120,000 had disappeared into the Confederacy, the purses of the rebels themselves, or to anyone who might have found cash along their escape route.

On The Streets

Raiders not assigned to rob the three banks guarded the streets, herded pedestrians onto the village green and rounded up horses for the getaway. Many of those who were in the vicinity that day, including those who were students at the St. Albans Academy (today’s home of the St. Albans Historical Museum) would later write accounts of the day.

Tight control of people and information on Main Street prevented men in the railroad machine shops and at the St. Albans Foundry, just a block or two away, from responding to any sort of alarm.

Six to eight persons already were being held on the park when Collins Huntington, a St. Albans resident, appeared on Main Street near the American House.

A raider touched him on the shoulder and ordered him to pass over to the holding area. Huntington, thinking the man was intoxicated or involved in some kind of prank, ignored him. The raider shot him and the ball struck Huntington in the back and glanced off a rib. Bleeding from his wound, Huntington crossed Main Street onto the park. He would survive the injury.

The bank robberies took only 12 to 15 minutes and meanwhile, other raiders stole horses from passersby, wagons, and hitching posts on Main Street.

One horse was stolen from Gilmore’s Livery Stable and several from Field’s and Fuller’s Livery Stables, all located on Lake Street. Proceeding north, raiders obtained saddles, bridles and saddle blankets from Bedard’s Harness shop on the east side of Main Street (north of Bank Street). More horses were stolen from Fuller’s other livery stable situated behind the Tremont House.

Leonard Bingham who came up Lake Street and onto Main Street, attempted to apprehend Young as he was mounting a stolen horse. He failed. About a dozen shots were fired at Bingham as he fled up Main Street, and he was slightly wounded in the abdomen.

Leonard L. Cross, a photographer with a shop on Main Street, heard the pistol shots, appeared at the door of his shop, and seeing a raider he later identified as Young, inquired as to what they were celebrating.

The Confederate replied, “I’ll let you know” and fired. The ball lodged in a door just missing Cross’ head.

Elinus Morrison, a contractor supervising the construction of the Welden House Hotel on Bank Street, just a block the east of Main Street, heard of the raid and ran with his men to see if they could help. Ordered by Young to stop, Morrison attempted to dodge into Miss Beattie’s Millinery Store. Young fired. The bullet pierced Morrison’s hand and abdomen.

Badly wounded, Morrison was given first aid at nearby Dutcher’s Drug store on Main Street and taken to his room at the American House. He died two days later.

At about the time Morrison was shot, more citizens were taking up weapons.

Wilder Gilson came onto Main Street with a rifle and fired at the last of the raiders who were in front of the Brainerd Block, now the site of Jeff’s restaurant at the corner of Main and Bank streets. Confederate raider Charles Higbee, was badly wounded. Aided by his companions, he escaped to Canada where he recovered from his wound.

The raiders tried to set other buildings on fire by hurling bottles of the incendiary mixture against them. But none worked as intended.

Chase is Given

Captain George Conger, a native of St. Albans and a resident of Lower Welden Street, had recently been discharged from the Union Army after 10 months of service in the Company B, First Vermont Cavalry. While downtown that day, he was informed of the raid, and come running up Main Street from the south. When raiders attempted to force him into the park, he broke away and escaped by running into the American House and out a side door onto Lake Street.

Conger, carrying a rifle provided to him by female passerby, made his way back to Main Street, and shot at a raider. The rifle failed to fire. Two raiders (Young and Higbee) returned fire on Conger, but both shots missed.

Having robbed the banks, the Confederates began to gather at the foot of Bank Street, next to the park. “During the period of their stay, they uttered fearful threats and a good deal of blasphemy. … They had fired their pistols many times with the greatest impunity,” stated a newspaper article.

In addition to photographer Cross and Conger, others, too, reported escaping harm. Elihu Jones, age 67, said a raider ordered him to stop and when he didn’t took aim and fired. The shot missed. George Nettleton had a pistol pointed at his head until he relented and gave up his hat to raider Collins, who in all the commotion had lost his.

Livery stable owner Erasmus Fuller came riding into town and saw his horses in the raiders’ hands. He demanded they be returned but backed down under loaded pistols and one raider’s threat: “If you don’t keep still, we will shoot you.”

Following the raid, bullet holes were present in downtown buildings and two windows had been hit at A.H. Munyan’s store, located just north of the Franklin County Bank. It was said that elm trees near the corner of Congress and Main streets probably still contained lead when they were cut down in the late 1970s or early 1980s.

The raiders, as they fled, tossed Greek Fire at the American House and other buildings, including Atwood’s Hardware Store, where later the liquid had to be chopped out in order to prevent fire.

Later, Young would write that he had every intention of burning Gov. Smith’s home, but with townspeople firing weapons – no matter how ancient the guns or how inept the marksmen – the Confederates had no alternative but to flee.

Acting in great haste, Capt. Conger, widely held as the local hero of the day, organized a posse of about 50 men who immediately took up pursuit. A second posse of about 40 men, organized by F. Stewart Stranahan and John W. Newton, also took to the chase.At the far north end of Main Street, the raiders picked up the plank road that ran between St. Albans and Sheldon. Today’s Missisquoi Valley Rail Trail follows the same path. By now it was too late and too dangerous to think of robbing Swanton and Sheldon banks.

Again using Greek Fire, the raiders tried to burn the wooden bridge across Black Creek at Sheldon. Area residents quickly extinguished it. Hotly pursued by Conger and his posse of mounted men and some in buggies, the raiders headed for Canada.

Among the pursuers was William Whiting of the St. Albans Messenger staff who wrote extensively about the raid and later the criminal trials. Many area residents along the raiders’ path spotted the fleeing rebels; one man had his horse stole from under him.

It is most likely that the raiders, about a mile north of Sheldon, broke up into at least two groups, one heading toward Franklin where it, too, divided with some traveling northwest out to Morse’s Line Road. The other party may have taken Tyler Branch Road at the intersection of Duffy Hill Road and crossed the Old Plank Bridge into Enosburg Village before riding out on what is now Golf Course Road to West Berkshire.

Some of the rebels are thought to have passed through West Enosburg on East Enosburg Road and Boston Post Road and into Berkshire before taking Vallancourt Road toward Canada. That route would have taken them very near today’s Dairy Center in Enosburgh.

As the chase was underway, a telegram had gone out from Vermont to the Canadian authorities alerting them to the robberies.

Conger said that gunfights erupted with some of the robbers and two were wounded. Neither that, nor a report that a Canadian bailiff was killed has been confirmed.

Bruce and Spurr were captured at Elder’s Tavern in Stanbridge, Quebec with more than $35,000 in loot. Collins and Lackey were nabbed there, too. St. Albans historian Carl Johnson also noted that Doty and McGrorty were found in a barn at Waterloo with about $1,000. Gregg, Wallace, Swager and Squire Tevis were caught in Frelighsburg, as was Young.

Young put up a fight inside a private house. Having been placed in a wagon, he knocked the driver off the seat and managed to drive a short distance before being recaptured.

Canadian authorities quickly had the border guarded by a militia force in order to prevent another raiding party from entering the country and angry Americans from coming north to seize the already captured men.

Within 24 hours, 14 of the raiders had been apprehended. They had just $87,000 in their possession.

Read more about the aftermath of the events of the St. Albans Raid.