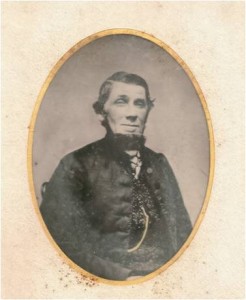

Captain George Conger is seen in this tintype photograph, the only known photo of him after the Civil War.

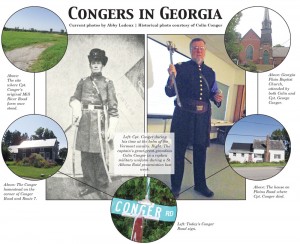

GEORGIA — On a warm night in late August, Colin Conger donned a wool jacket and unsheathed a long sword. He looked prepared to mount a horseback and ride through the night. Instead, he was here to give a presentation at the Georgia Public Library.

Conger is the great-great-grandson of Captain George Parker Conger, a hero of the St. Albans Raid. As the 150th anniversary of the northernmost land action in the Civil War approaches, Conger dressed in period garb replicated from the only two photographs known to exist of his ancestor.

A former Georgia selectman largely involved with the historical society, Conger has carefully chronicled the captain’s history and important role in the raid. He relayed the story to a captivated audience last Wednesday, explaining his motive before the presentation began.

“I was watching the news one evening, and they were interviewing college students on spring break,” Conger said. “They went up to [one student] and said, ‘Who won the Civil War?’ She looked at him and said, ‘the French?’”

The room erupted in laughter, but Conger had a serious message behind the anecdote.

“People need to understand about the Civil War – all wars, but the Civil War in particular,” he said. He clicked through his slideshow, showing the total casualties of war. All American battles saw 696,000 casualties, but the Civil War alone claimed an estimated 600,000.

“Think about that for a second,” Conger said, and the gravity set in. “The population of the U.S. was 35 million at the time … if we were to have the same [proportion of casualties today], 6.5 million people would be gone.”

The Raid

Though Captain Conger’s status was sealed in the raid, he’d already made an impression. Founder of the Ransom Guard with famed Gen. George Stannard, he also raised a company of the 1st Vermont Cavalry, which saw several battles at the war’s start.

In 1864, the raid was hatched to draw northern troops out of the devastated south and into the Union after military setbacks “virtually crippled the Confederacy,” Conger said.

Confederate officers chose Vermont due to its vocal support of the Union cause. One Confederate official said, “We should dig a ditch around Vermont and float it out to sea,” Conger quoted.

Bennett Young, a Confederate officer from Kentucky, led 22 men on their mission, said Conger. They trickled into the hub of Franklin County one or two at a time with various cover stories so as not to stir northern suspicion. They were instructed to disguise their southern accents.

“If nothing else, may I destroy the northern border of Vermont and New Hampshire for 150 miles?” Young wrote to his Confederate officers.

That was his intent on the cloudy Wednesday in October. The raiders armed themselves with pistols to rob three banks and four-ounce bottles of “Greek fire” – liquid phosphorous – to burn the city down, rendered ineffective by the steady drizzle that day.

On stolen horses, the Confederates rode in and stole $217,000. They shot one man, some said he was a Confederate sympathizer, visiting from New Hampshire. He later died from his wounds.

From his house on Fairfield Street, Captain Conger heard the commotion below and ran out, unarmed, to confront it. He encountered Young, who recognized the captain’s military status and informed him, “You are my prisoner.”

“Well, one thing I got from my grandfather that has carried on to me … you don’t just tell me something,” Conger said. “It doesn’t work that way.”

Captain Conger escaped his captor and alerted the townspeople to grab their guns. The chase was on.

The audience listened intently as Conger continued the tale, which proceeded with Captain Conger and a 50-man posse pursuing the fleeing raiders into Canada.

“[The raiders thought], ‘we made it; no one’s going to be crazy enough to come across the border after us, right?’” Conger said. “Forgot about one man: Conger.”

In Canada, the captain captured Young, who he hoped to subject to “a first-class hanging,” back home, Conger said.

But a British captain persuaded the group to bring Young to Quebec, where five other rebels were reportedly held. The captain relinquished his prisoner at a British garrison, conscious of the tension surrounding British neutrality in the war.

“That was totally against his nature,” Conger said, but added it was probably the captain’s most important action in the raid. “He was a very brave man. He would have fought ’til the death, but he thought that was the right thing to do.”

A Canadian judge refused to extradite the raiders, who never stood trial in the U.S. By 1865, Conger reported, they were free of all legal concerns.

After the raid, six disappeared; one made it back to the South posing as a woman, and many became successful bankers – one even founded the First National Bank of Fort Worth.

“It is said that they got their start in banking in St. Albans,” Conger jested.

The aftermath

The stolen cash largely inconsequential, and the Confederates’ overarching plan failed, the St. Albans Raid had no real impact on the war, Conger said.

Next month, St. Albans will host a four-day commemoration for the raid, complete with reenactments, demonstrations and a costume ball.

Conger will attend in his Civil War-era captain’s garb. Accompanying him will be another guest of honor: Young’s only known surviving relative. Conger joked he’d ask her to surrender upon their meeting.

Pranks aside, Conger will let 150-year-old bygones be bygones.

“I’m looking forward to seeing her,” he said. “It was wartime. Things happen in war.”

The Georgia Congers

After the war, Captain Conger moved from St. Albans to Georgia, where he farmed land at the corner of present-day Mill River Road and Ethan Allen Highway. He then bought the still-standing Conger homestead on the aptly named Conger Road.

His only son, Stephen, Colin Conger’s great-grandfather, operated that farm for many years.

The Conger family also donated land for a school, named the Conger School in the family’s honor.

Following the captain’s third marriage to Mary Bliss – he was already twice widowed – Captain Conger attended the Georgia Plains Baptist Church, despite his history as a Methodist. When the church burned in 1886, Captain Conger bought pew 21 to support its reconstruction.

A century later, in 1986, Colin Conger and his wife moved to Georgia Plains to be closer to their respective jobs. They started attending the Baptist church down the road, and Conger recalled feeling comfortable in a pew in the back of the church, which became his post.

During research for the church’s 100-year anniversary, Conger uncovered the document detailing his great-great-grandfather’s purchase of pew 21.

“Guess what? We were sitting in it,” he said, still amazed.

Today, Conger remains in Georgia, his surname nothing short of a legacy here. He will honor that at the raid anniversary next month, which will now see a few more attendants, as Conger’s audience expressed excitement following his presentation.

“This has been most interesting,” said one woman who moved to Georgia after marrying. “I wasn’t going to pay any attention to the raid [anniversary] … well, now I can’t wait …”

By ABBY LEDOUX

Milton Independent

Colin Conger and a distant relative of Confederate Bennett Young will be recognized during the raid re-enactments on Saturday, Sept. 20 (2 p.m.) and Sunday, Sept. 21 (1 p.m.) in Taylor Park in St. Albans.

One Response to Georgia family’s line traces back to raid